2024-115 The Division of Occupational Safety and Health

Process Deficiencies and Staffing Shortages Limit Its Ability to Protect Workers

Published: July 17, 2025Report Number: 2024-115

July 17, 2025

2024‑115

The Governor of California

President pro Tempore of the Senate

Speaker of the Assembly

State Capitol

Sacramento, California 95814

Dear Governor and Legislative Leaders:

As directed by the Joint Legislative Audit Committee, my office conducted an audit of the Division of Occupational Safety and Health (Cal/OSHA) and its efforts to enforce health and safety standards that protect California’s nearly 20 million workers. We reviewed 60 case files that Cal/OSHA handled from fiscal years 2019–20 through 2023–24 and found deficiencies in Cal/OSHA’s enforcement processes and staffing levels that may undermine some of California’s workplace protections.

In general, we determined that Cal/OSHA did not demonstrate that it had sufficient reasons for closing some workplace complaints and accidents without conducting an on‑site inspection. In nine of the 30 uninspected complaints we reviewed, we questioned Cal/OSHA’s rationale for deciding not to inspect because the case files lacked evidence to support that Cal/OSHA had complied with its own policies. Some accident cases also lacked support for Cal/OSHA’s decision not to inspect.

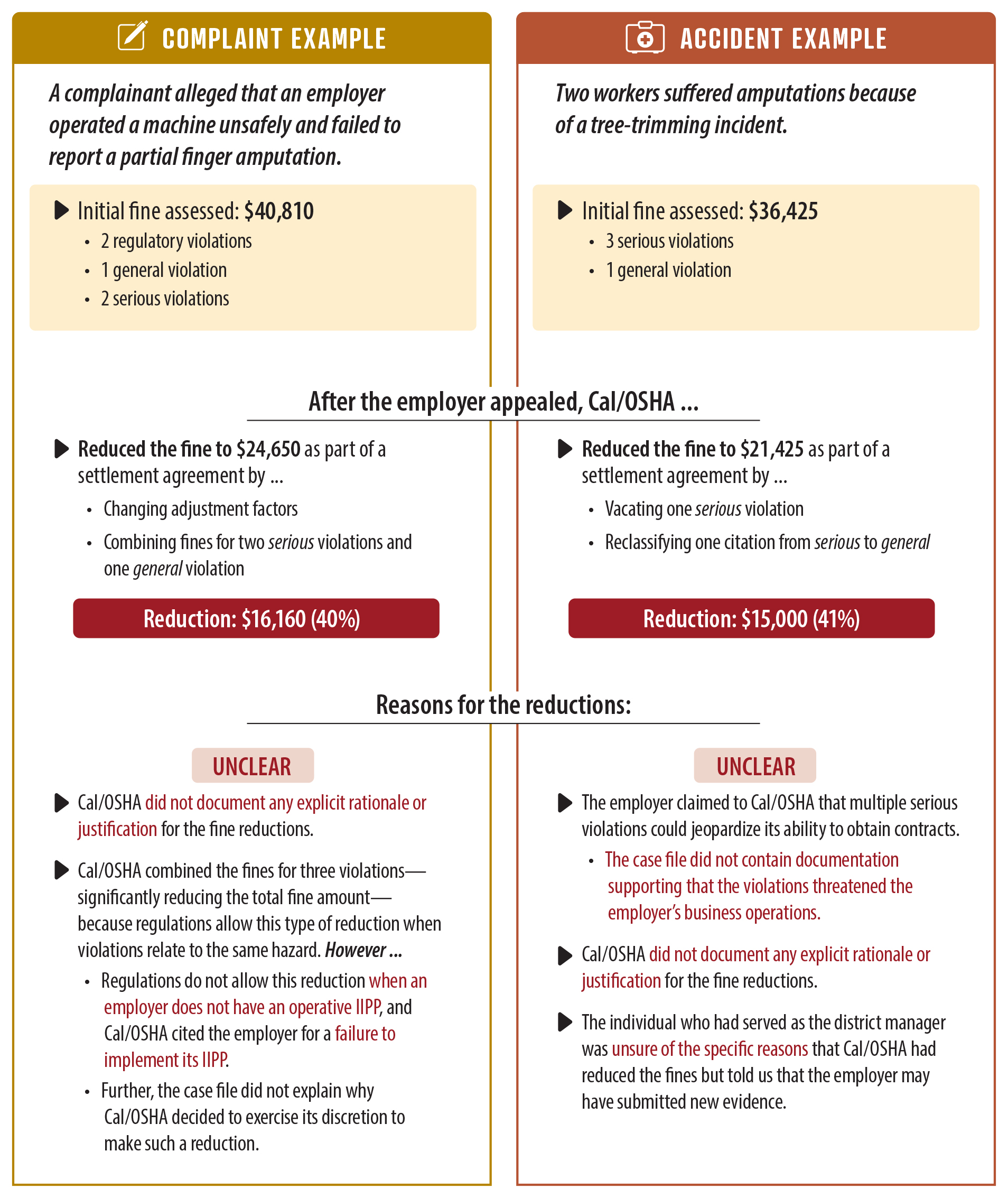

We also observed some critical weaknesses among the on‑site inspections that Cal/OSHA did conduct. Cal/OSHA did not consistently document effective reviews of employers’ injury and illness prevention programs, causing us to question whether it may have overlooked potential violations in some instances. When Cal/OSHA identified hazards and cited employers for violations, it did not always document that those employers had abated the hazards. Furthermore, the fines that Cal/OSHA assessed employers were sometimes less than the violations may have warranted, and Cal/OSHA often did not document a clear rationale for further reducing fines in post‑citation negotiations with employers.

Cal/OSHA’s process deficiencies and staffing shortages are root causes for many of the concerns we identified. Cal/OSHA has left key policy documents unrevised for years, conducted internal audits inconsistently, and relied on paper‑based case files. Cal/OSHA had a 32 percent vacancy rate in fiscal year 2023–24 and even higher vacancy rates in many of its district offices, significantly limiting its ability to protect workers.

Respectfully submitted,

GRANT PARKS

California State Auditor

Selected Abbreviations Used in This Report

| Cal/OSHA | Division of Occupational Safety and Health |

| DIR | Department of Industrial Relations |

| Federal OSHA | Occupational Safety and Health Administration |

| IIPP | Injury and illness prevention program |

Summary

Key Findings and Recommendations

The Division of Occupational Safety and Health—better known as Cal/OSHA—is the division of the Department of Industrial Relations (DIR) tasked with protecting and improving the health and safety of California’s nearly 20 million workers by enforcing the workplace protections state law requires employers to provide. This enforcement process, which was the focus of our audit, generally involves Cal/OSHA personnel deciding whether to conduct an on‑site inspection of a workplace—typically after receiving a health or safety complaint or learning of a worker fatality, injury, or illness (accident)—and issuing citations and fines according to the results of the inspection. Our audit included a review of 60 case files that Cal/OSHA handled between fiscal years 2019–20 and 2023–24, and we found deficiencies in Cal/OSHA’s processes and staffing levels that may undermine some of California’s workplace protections.

Cal/OSHA Did Not Inspect Some Complaints and Accidents, Despite Evidence That an Inspection May Have Better Protected Workers

Of the 60 case files we reviewed, 30 related specifically to Cal/OSHA’s decision‑making about whether an on‑site inspection was necessary for a complaint. In nine of those 30 cases, we question Cal/OSHA’s rationale for deciding not to conduct on‑site inspections. In at least five additional cases, Cal/OSHA followed its policies in deciding not to inspect on‑site, but we found factors indicating that inspections may have helped better protect workers. Further, when Cal/OSHA investigated complaints by letter—essentially, by sending the employer a letter requesting that it address alleged hazards—Cal/OSHA often closed cases even when it lacked sufficient supporting evidence that the employer had addressed all the alleged hazards.

We also reviewed case files for seven accidents that Cal/OSHA decided not to inspect and had concerns about Cal/OSHA’s decision in six of them, mainly because the case files lacked a clear rationale for why inspections were unnecessary. Cal/OSHA has broad statutory authority to inspect accidents, but state law and Cal/OSHA’s policies require inspections only of fatalities or of cases with the most severe injuries. In the cases we reviewed, workers sometimes sustained injuries that required emergency medical treatment, yet Cal/OSHA did not investigate the causes of those accidents.

When It Does Perform Inspections, Cal/OSHA’s Process Has Critical Weaknesses

Among the on‑site inspections Cal/OSHA did perform, we observed some common weaknesses. For example, the case files we reviewed were not always thorough enough to support Cal/OSHA’s decision‑making. Notably, Cal/OSHA enforcement personnel did not consistently document effective reviews of employers’ injury and illness prevention programs—which are key safeguards against dangerous hazards—nor did they include in the case files detailed notes from interviews they conducted with workers. Further, Cal/OSHA took weeks or even months to initiate some inspections of complaints and accidents: in two cases, it took over a month to initiate inspections of complaints when state law required inspections to begin within three working days.

Cal/OSHA Could Better Ensure That Employers Maintain Safe Workplaces

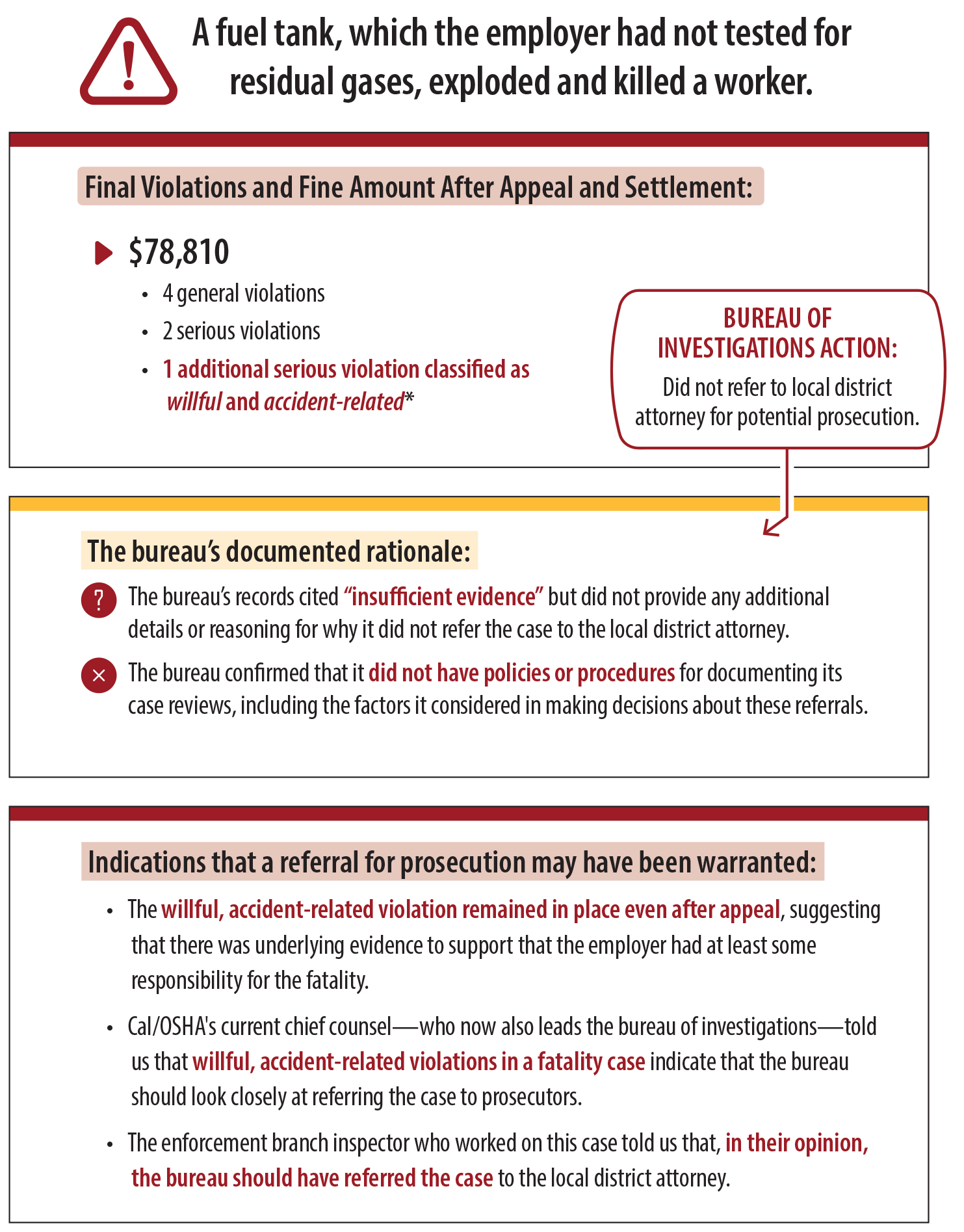

By conducting on‑site inspections, Cal/OSHA can require abatement of violations it identifies, issue citations and fines to employers, and sometimes refer cases to prosecutors if employers’ violations may have been criminal in nature. However, we identified shortcomings in each of these areas. The complaint and accident inspections we reviewed often lacked supporting evidence that employers had abated violations, reducing assurances that workers were safer as a result of those inspections. In addition, Cal/OSHA’s initial fine determinations for some complaint and accident inspections were less severe than regulations and policy may have warranted, such as one worker fatality for which Cal/OSHA assessed a $21,000 fine but may have been able to fine the employer nearly twice as much. Cal/OSHA often did not document a clear rationale for its decisions to reduce fines in post‑citation negotiations with employers, such as by explaining why reductions were reasonable given the employer’s assertions. Further, Cal/OSHA’s bureau of investigations did not document that it performed its own reviews of some accidents and, for others that it did review, it did not clearly explain why it chose not to refer them for potential criminal prosecution.

Cal/OSHA Must Address Shortcomings in Its Staffing Levels and Oversight

Understaffing and process deficiencies are root causes for many of the concerns we identified. Cal/OSHA had a 32 percent vacancy rate in fiscal year 2023–24, and its vacancy rate was even higher in its enforcement branch. Nearly all 24 regional and district managers we interviewed told us that their offices would have conducted more on‑site inspections and inspected more thoroughly if their offices had been adequately staffed. Compounding the effects of understaffing, many of Cal/OSHA’s policies and procedures have been out‑of‑date for years. In addition, Cal/OSHA did not consistently conduct ongoing audits of its case files to ensure that staff were implementing its policies and procedures correctly. Cal/OSHA’s processes have been largely paper‑based, which is inefficient and increases its risk of having poor case file documentation.

To address these findings, we have made recommendations to Cal/OSHA to update its policies, modernize and document its procedures, and increase its staffing levels so that it can conduct more on‑site inspections of workplaces and better protect workers.

Agency Comments

DIR indicated it would implement our recommendations and provided additional context about the efforts it has been making to address the concerns we identified.

Introduction

Background

Both federal and state law require employers to provide safe and healthy workplaces and to do anything reasonably necessary to protect the life, safety, and health of workers. The federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration (federal OSHA) oversees Cal/OSHA in its efforts to ensure that employers provide such workplace protections for workers in California. Cal/OSHA is tasked with protecting and improving the health and safety of California’s nearly 20 million workers and, with limited exceptions, has broad jurisdiction over nearly every workplace in the State. Employers in California must abide by workplace regulations that the Occupational Safety and Health Standards Board sets and that Cal/OSHA enforces. In addition to its enforcement efforts, which were the subject of this audit, Cal/OSHA also performs functions such as providing education and outreach to employers and workers and issuing permits for elevators and amusement rides.

Cal/OSHA’s Enforcement of Workplace Health and Safety

Cal/OSHA’s enforcement of workplace health and safety standards involves a process consisting of three key stages, as Figure 1 shows. The process generally involves deciding whether to conduct an on‑site inspection of a workplace—typically after receiving a workplace health or safety complaint or learning of an accident—and issuing citations and fines according to the results of the on‑site inspection.

Figure 1

Cal/OSHA’s Enforcement Process Includes Three Key Stages

Source: State law and Cal/OSHA policies and procedures.

Figure 1 shows the three stages of Cal/OSHA’s enforcement process. First, Cal/OSHA receives notification of potential workplace hazards and determines whether to conduct an on-site inspection. The two main types of cases that Cal/OSHA investigates are complaints and accidents. Workers, union officials, or anyone else can report a workplace health or safety concern to Cal/OSHA by filing a complaint. Employers and first responders are required to report accidents – fatalities and serious injuries or illnesses – to Cal/OSHA. For example, if an employer has not provided training for how to use machinery, putting workers at risk, anyone could report this to Cal/OSHA as a complaint, but if an employee was injured by machinery and treated at a hospital, the employer and first responder would be required to report this to Cal/OSHA as an accident. Next, Cal/OSHA may conduct an on-site inspection to determine whether workplaces are free from occupational safety and health hazards. Key steps in the on-site inspection process include at least one Cal/OSHA inspector visiting the worksite, (usually unannounced). The inspectors will conduct interviews, take photos, gather other evidence, and request documents from employers, then they analyze the evidence and determine whether the employer has violated any workplace regulations. Finally, Cal/OSHA issues citations, assesses fines, and takes other actions to ensure that employers address any violations Cal/OSHA identified. Employers can appeal Cal/OSHA’s citations and fines. Cal/OSHA’s bureau of investigations separately investigates some accidents for potential criminal conduct, and can refer these cases to local prosecutors.

Cal/OSHA has an enforcement branch that carries out this process. As of 2024, the enforcement branch consisted of 17 district offices across the State that handled most inspections.1 Four regional offices, each with a regional manager, oversaw these 17 district offices. The enforcement branch also has other specialized offices and units that usually focus on particular types of workplaces or inspections, such as offices focused on employers that conduct mining and tunneling. A district office or specialized unit typically has a district manager who oversees the office or unit, certified safety and health officials (inspectors) who conduct inspections, and support staff.

Cal/OSHA’s legal unit also plays an important role in the enforcement process, including by advising and assisting enforcement personnel. Within the legal unit is the bureau of investigations, which coordinates with enforcement personnel and prepares certain accident cases for referral for potential criminal prosecution to the appropriate prosecutorial authority, such as a local district attorney. Such authorities can then prosecute employers for negligently or willfully violating workplace safety or health standards, which can result in criminal sanctions, such as imprisonment or additional fines. The bureau of investigations may work on a case concurrently with the enforcement branch or after the enforcement branch has completed its on‑site inspection. The bureau’s work is separate from the enforcement branch’s inspections and citations.

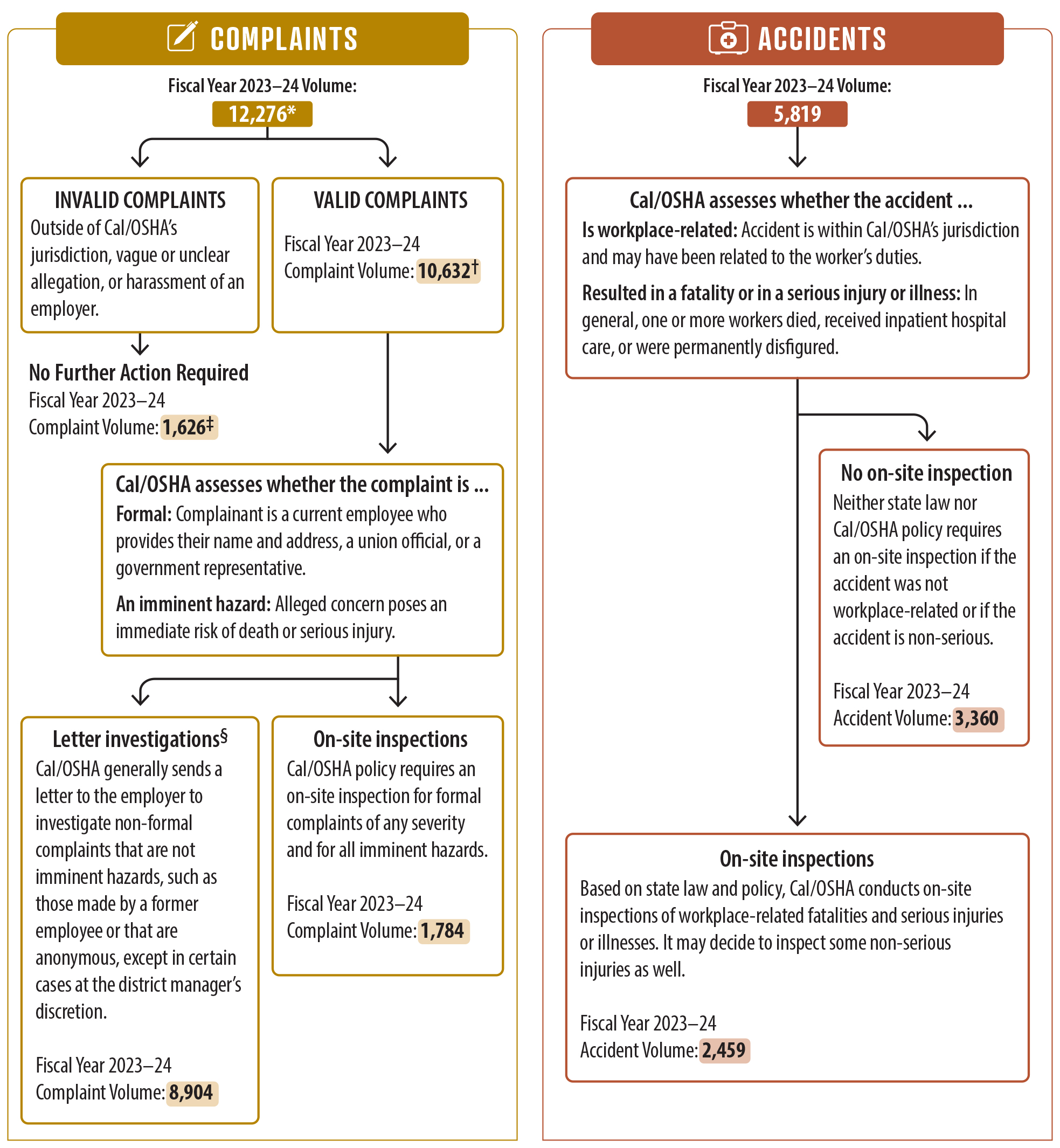

When determining whether to conduct an on‑site inspection, Cal/OSHA enforcement personnel assess a variety of factors. As Figure 2 shows, these factors vary substantially between complaints and accidents. One factor that is unique to complaints, for instance, is the source of the complaint: Cal/OSHA policy categorizes complaints as either formal or non‑formal depending on who makes the complaint, and this categorization can affect whether Cal/OSHA conducts an on‑site inspection.

Figure 2

Cal/OSHA’s Intake Processes for Complaints and Accidents Involve Weighing Different Factors to Determine Whether an Inspection is Necessary

Source: State law, Cal/OSHA policies and procedures, and OSHA Information System (OIS) data.

* Of the 12,276 complaints received in fiscal year 2023–24, Cal/OSHA deemed 10,632 as valid, 1,626 as invalid, and did not categorize the remaining 18 complaints, of which it performed on‑site inspections for two of these uncategorized complaints.

† Cal/OSHA conducted both a letter investigation and an on‑site inspection for 133 of the valid complaints it received, and we included these complaints in both categories. Further, Cal/OSHA did not conduct either a letter investigation or an on‑site inspection for 77 of the valid complaints it received.

‡ Of the 1,626 complaints Cal/OSHA deemed as invalid, it nevertheless conducted either a letter investigation, an on‑site inspection, or both for 30 of these complaints. We did not include these 30 complaints in our counts of letter investigations or on-site inspections.

§ Letter investigations can be followed by on‑site inspections depending on the employer’s response to Cal/OSHA’s letter.

Figure 2 shows Cal/OSHA’s intake processes for complaints and for accidents. In Fiscal Year 2023-24, Cal/OSHA received a volume of 12,276 complaints. These are divided into invalid complaints, which are outside of Cal/OSHA’s jurisdiction, vague or unclear allegations, or constitute harassment of an employer; and valid complaints. In Fiscal Year 2023-24, Cal/OSHA received a volume of 1,626 invalid complaints, and 10,632 valid complaints. If Cal/OSHA determines that the complaint is invalid, no further action is required. If the complaint is valid, Cal/OSHA then assesses whether the complaint is formal. A complaint is formal if the complainant is a current employee who provides their name and address, a union official, or a government representative. Cal/OSHA also assesses if the alleged concern in the complaint poses an immediate risk of death or serious injury – called an “imminent hazard.” Cal/OSHA policy requires an on-site inspection for formal complaints of any severity, and for all imminent hazards. In Fiscal Year 2023-24, Cal/OSHA’s volume of formal and/or imminent hazard complaints was 1,784. Cal/OSHA generally conducts letter investigations – it sends a letter to the employer to investigate – all non-formal complaints that are not imminent hazards, such as those made by a former employee or those that are anonymous, except in certain cases at the district manager’s discretion. In Fiscal Year 2023-24, Cal/OSHA’s volume of complaints in this category was 8,904. However, our analysis of Cal/OSHA’s data included some anomalies, such as 18 complaints that were apparently not categorized as valid or invalid, so the total numbers represented in this portion of the diagram do not add up correctly. Cal/OSHA also received a volume of 5,819 accident reports in Fiscal Year 2023-24. Cal/OSHA first assesses whether the accident is workplace related – within Cal/OSHA’s jurisdiction, and may have been related to the worker’s duties – and whether it resulted in a fatality or serious injury or illness. In general, this means one or more workers died, received inpatient hospital care, or were permanently disfigured. Based on state law and policy, Cal/OSHA conducts on-site inspections of workplace-related fatalities and serious injuries or illnesses. It may decide to inspect some non-serious injuries as well. Neither state law nor Cal/OSHA policy requires an on-site inspection if the accident was not workplace-related or if the accident is non-serious. In Fiscal Year 2023-24, Cal/OSHA received reports of 3,360 accidents that it did not inspect on-site, and reports of 2,459 accidents that it did inspect on-site.

State law prescribes time frames by which Cal/OSHA must investigate complaints from certain sources, as the text box shows. However, state law does not necessarily require Cal/OSHA to conduct on‑site inspections of these complaints. Cal/OSHA has developed an alternative option for investigating complaints by which enforcement personnel send a letter to the employer outlining the complaint’s allegations and requesting that the employer investigate them, address any hazards it identifies, and respond to Cal/OSHA in writing with the results of these efforts. Cal/OSHA refers to this option as an investigation by letter (letter investigation). Depending on the employer’s response to Cal/OSHA’s letter, letter investigations can still result in an on‑site inspection.

State Law Requires Cal/OSHA to Respond to Complaints Within Certain Time Frames

If Cal/OSHA receives a complaint from an employee, an employee’s representative, or certain others, it must investigate the complaint as soon as possible, but not later than:

- 24 hours for complaints from law enforcement or from a prosecutor.

- 3 working days after receipt of a complaint alleging a serious violation.

- 14 calendar days after receipt of a complaint alleging a non‑serious violation.

A serious violation means that there is a realistic possibility that death or serious physical harm could result from the alleged hazard. All other complaints are deemed to allege non‑serious violations.

Source: Labor Code section 6309.

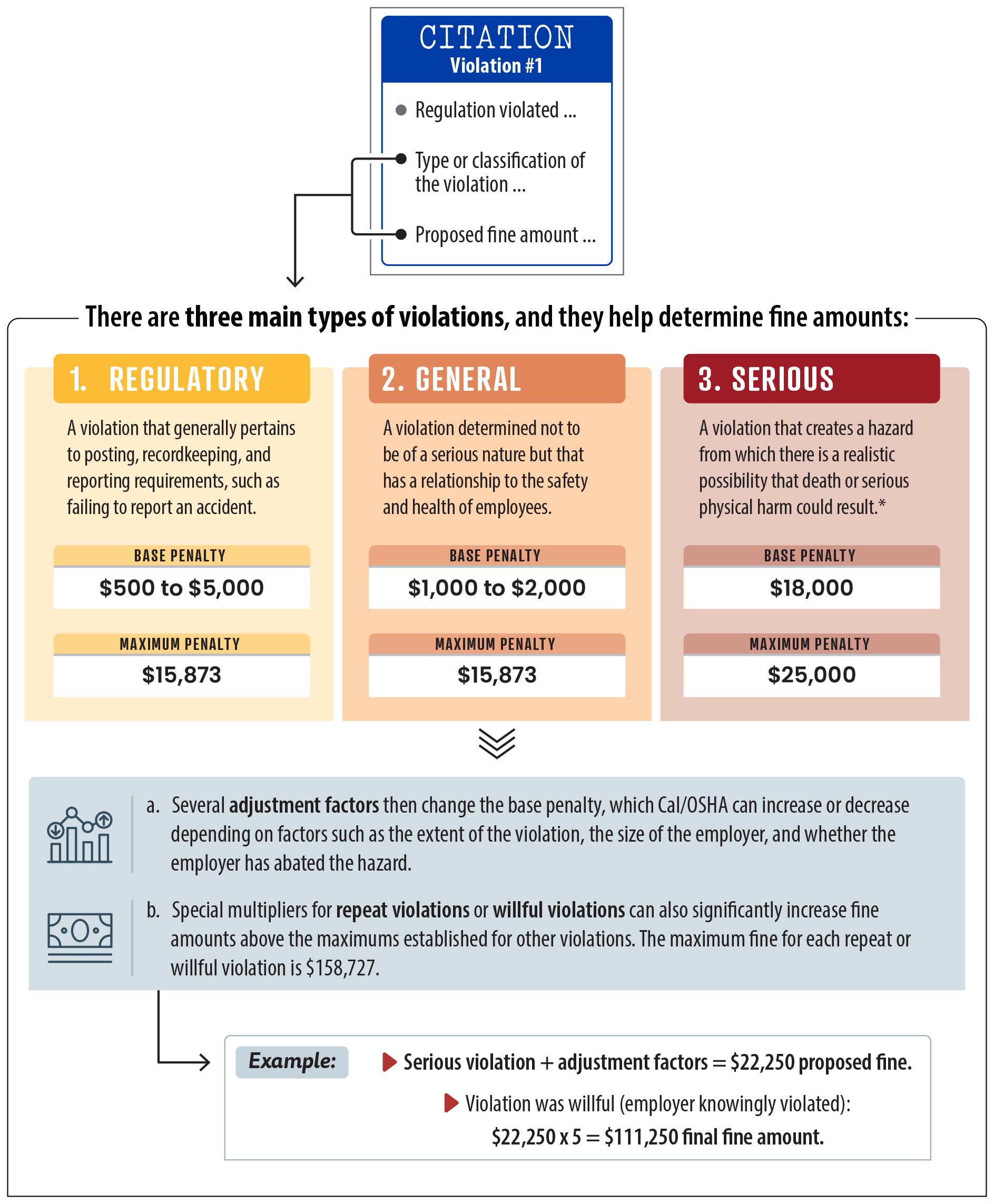

When Cal/OSHA decides it is appropriate to do so, it conducts an on‑site inspection to determine whether an employer has violated any workplace regulations and, if so, it issues citations and fines. In addition to responding to complaints and accidents, Cal/OSHA also conducts on‑site inspections in other instances. For example, it conducts targeted or programmed inspections (proactive inspections) for certain industries, such as mining and tunneling, or according to certain indicators, such as when employers obtain permits for construction. Regardless of the type of on‑site inspection that Cal/OSHA conducts, it gathers and documents evidence to determine whether any workplace violations exist and it issues citations within six months of the violations occurring. As Figure 3 shows, workplace violations generally fall into three categories that result in different fine amounts, and an inspection can result in multiple violations and fines. From fiscal years 2019–20 through 2023–24, about two‑thirds of Cal/OSHA’s on‑site inspections resulted in at least one fine.

Figure 3

Cal/OSHA’s Citations Include the Type of Violation and the Fine Amount

Source: State law, Cal/OSHA policies and procedures, and case files.

* State law defines serious physical harm as any workplace injury or illness that results in inpatient hospitalization for purposes other than medical observation; the loss of any member of the body; any serious degree of permanent disfigurement; or impairment sufficient to cause a part of the body or the function of an organ to become permanently and significantly reduced in efficiency on or off the job, such as, depending on the severity, crushing injuries, respiratory illnesses, or broken bones.

Figure 3 shows how Cal/OSHA calculates the fine amount based on the type of violation it issues. For example, Violation #1 in a citation would include the regulation violated, the type or classification of the violation, and the proposed fine amount. There are three main types of violations, and they help determine the fine amounts. A regulatory violation generally pertains to posting, recordkeeping, and reporting requirements, such as failing to report an accident. A general violation is one that is determined not to be of a serious nature, but that has a relationship to the safety and health of employees. A serious violation creates a hazard from which there is a realistic possibility that death or serious physical harm could result. The base penalty for a regulatory violation is $500 to $5,000, with a maximum penalty of $15,873; the base penalty for a general violation is $1,000 to $2,000, also with a maximum penalty of $15,783; and the base penalty for a serious violation is $18,000, with a maximum penalty of $25,000. Several adjustment factors then change the base penalty, which Cal/OSHA can increase or decrease depending on factors such as the extent of the violation, the size of the employer, and whether the employer has abated the hazard. Special multipliers for repeat violations or willful violations can also significantly increase fine amounts above the maximums established for other violations. The maximum fine for each repeat or willful violation is $158,727. For example, a serious violation plus adjustment factors might total a proposed fine of $22,250. If the violation was willful (the employer knowingly violated the safety standard), the proposed fine would be multiplied by 5, for a total fine amount of $111,250.

Upon receiving a citation from Cal/OSHA, an employer has 15 working days to appeal the citation or else it becomes final. Federal OSHA reported that in fiscal year 2022–23, employers appealed nearly half of all citations. If the employer appeals, the case then enters a process largely overseen by the Occupational Safety and Health Appeals Board (appeals board), which is a three‑member, quasi‑judicial body within DIR that is independent from Cal/OSHA. During this process, Cal/OSHA and the employer can negotiate a settlement agreement, which is an order signed by an administrative law judge that finalizes the case and the terms of any violations and fines. If the parties do not reach an agreement, the appeals board provides an opportunity for a formal hearing and issues a final decision. Hearings are relatively rare: for example, according to federal OSHA, the appeals board closed nearly 2,300 appealed cases during fiscal year 2022–23 but oversaw fewer than 100 hearings that year.

The Joint Legislative Audit Committee requested that we evaluate Cal/OSHA’s oversight and enforcement efforts, including how it handles complaints and assesses fines. As the text box shows, we reviewed 60 case files that form the basis of our work in several report sections.

We Reviewed a Total of 60 Case Files

Our selection consisted of:

45 complaints

- 30 complaints without an on‑site inspection.

– 6 invalid complaints

– 24 letter investigations

- 15 complaints with an on‑site inspection.

15 accidents

– 7 accidents without an on‑site inspection.

– 8 accidents with an on‑site inspection.

Source: Selected case files covering our audit period of fiscal years 2019–20 through 2023–24.

Audit Results

- Cal/OSHA Did Not Inspect Some Complaints and Accidents, Despite Evidence That an Inspection May Have Better Protected Workers

- When It Does Perform Inspections, Cal/OSHA’s Process Has Critical Weaknesses

- Cal/OSHA Could Better Ensure That Employers Maintain Safe Workplaces

- Cal/OSHA Must Address Shortcomings in Its Staffing Levels and Oversight

Cal/OSHA Did Not Inspect Some Complaints and Accidents, Despite Evidence That an Inspection May Have Better Protected Workers

Key Points

- We questioned Cal/OSHA’s rationale for deciding not to inspect complaints in nine of the 30 cases we reviewed because the case files lacked evidence to support that Cal/OSHA had complied with its policies for making these decisions. In at least five additional complaints we reviewed, Cal/OSHA followed its policies in deciding to investigate by letter rather than inspect on‑site, but the circumstances of the cases, such as observable hazards or a history of complaints, suggested that inspections may have benefited workers more than the letter investigations did.

- Cal/OSHA often lacked assurance that employers had addressed the hazards alleged in complaints. In 15 of 24 letter investigations we reviewed, Cal/OSHA closed complaint cases without receiving or documenting sufficient evidence to support that the employer took steps to improve worker safety. Further, in 11 of the 24 letter investigations, employers did not respond in a timely manner—in two cases taking more than 50 days to respond—resulting in Cal/OSHA having limited assurance that employers had taken appropriately swift action to protect their workers.

- In six of the seven uninspected accident cases we reviewed, the case files lacked documentation to support Cal/OSHA’s decision not to inspect. In one case, a worker suffered a laceration that resulted in surgery and an overnight hospital stay, but the case file did not contain any explanation for why the injury did not warrant an inspection. In addition, although Cal/OSHA has broad statutory authority to inspect accidents, state law and Cal/OSHA’s policies require inspections of only fatalities or cases with the most severe injuries, meaning that Cal/OSHA may miss opportunities to correct workplace violations that cause less severe injuries—such as a skull fracture that rendered a worker unconscious but did not necessarily require inpatient hospital care—or that pose ongoing risks to workers.

Cal/OSHA Did Not Always Sufficiently Document Its Reasons for Deciding Not to Perform On‑Site Inspections of Complaints

There are two ways in which Cal/OSHA may handle a complaint without conducting an on‑site inspection: Cal/OSHA might determine that the complaint is invalid—if, for example, the complaint does not allege a workplace violation or if it is outside of Cal/OSHA’s jurisdiction—or Cal/OSHA may decide to investigate a valid complaint by sending a letter to the employer. Figure 2 in the Introduction describes Cal/OSHA’s process for making these determinations. During fiscal year 2023–24, Cal/OSHA classified 13 percent of the complaints it received as invalid and investigated 82 percent of the valid complaints it received with a letter instead of an on‑site inspection.

Although there are benefits to letter investigations, as the text box outlines, letter investigations are not a substitute for on‑site inspections. Cal/OSHA policy acknowledges this trade‑off by stipulating situations in which letter investigations cannot be used, such as when a complaint alleges an immediate risk of death or serious physical harm.

Letter Investigations Have Benefits and Drawbacks Compared to On‑Site Inspections

Potential benefits of letter investigations:

- Can be an efficient way for Cal/OSHA to respond to less serious hazards.

- Allows Cal/OSHA to interact with more employers about safety and health concerns.

- Can result in employers addressing hazards more quickly.

Potential drawbacks of letter investigations:

- Cal/OSHA may miss the opportunity to observe and address hazards that are not specifically included in the complaint.

- Employers essentially investigate themselves, which increases the risk that the hazard may remain uncorrected.

- Letter investigations cannot include citations or fines, which only result from on‑site inspections.

Source: Cal/OSHA policies and procedures and interviews with Cal/OSHA managers.

In Nine Cases, Cal/OSHA Lacked Evidence to Support Its Decision Not to Inspect On‑Site

To evaluate Cal/OSHA’s reasoning for deciding not to conduct on‑site inspections of complaints, we reviewed 30 case files for complaints that Cal/OSHA did not inspect: six complaints that it classified as invalid and 24 complaints that it found valid but investigated with a letter. We compared Cal/OSHA’s decision‑making in these cases to its internal policies that govern its complaint evaluation and documentation. Figure 4 details our conclusions. We question Cal/OSHA’s rationale for deciding not to inspect complaints in nine of the 30 cases—two of the six invalid cases and seven of the 24 letter investigations—because the case files lacked evidence to support that Cal/OSHA had complied with its own policies for making these decisions. These nine complaints included hazards that ranged in severity from allegations of impalement risks and unguarded machinery to allegations of poor ventilation and contaminated drinking water. However, in each case, an on‑site inspection could have helped ensure that the workplace was safe. Further, by not inspecting these cases, Cal/OSHA missed opportunities to hold employers accountable through citations and fines.

Figure 4

Two‑Thirds of the Uninspected Complaints We Reviewed Lacked Either Evidence Supporting the Initial Decision Not to Inspect or a Sufficient Employer Response

Source: Case files and Cal/OSHA policies and procedures.

We reviewed six complaints that Cal/OSHA determined to be invalid and 24 complaints that Cal/OSHA investigated by letter, for a total of 30 cases, and we found…

• Nine files lacked evidence supporting Cal/OSHA’s decision not to inspect on-site, causing us to question whether it should have done so.

• 11 files contained evidence supporting the initial decision not to inspect, but lacked a sufficient employer response to Cal/OSHA’s letter. As a result, it was unclear whether the decision to conduct a letter investigation had protected workers effectively.

• 10 files contained evidence supporting Cal/OSHA’s decision not to inspect and, for letter investigations, contained an employer response with evidence that it had addressed all alleged hazards.

Invalid Complaints (6) <h1>

• 2 case files lacked evidence to support classifying the complaint as invalid.

• 4 case files contained evidence supporting the complaint as invalid.

Letter Investigations (24) <h1>

Initial Decision to Inspect <h2>

• 7 case files lacked evidence to support Cal/OSHA’s decision not to conduct an on-site inspection.

• 17 case files contained evidence supporting Cal/OSHA’s decision to investigate by letter rather than conducting an on-site inspection.

Employer Response to the Letter Investigation <h2>

• 3 of the 7 case files that had lacked evidence to support Cal/OSHA’s decision not to conduct an on-site inspection had a sufficient employer response to Cal/OSHA’s letter.

• 15 case files either had no employer response or had an employer response that did not provide evidence that the employer had addressed all alleged hazards.

• 6 of the 17 case files that contained evidence supporting Cal/OSHA’s decision to investigate by letter had a sufficient employer response.

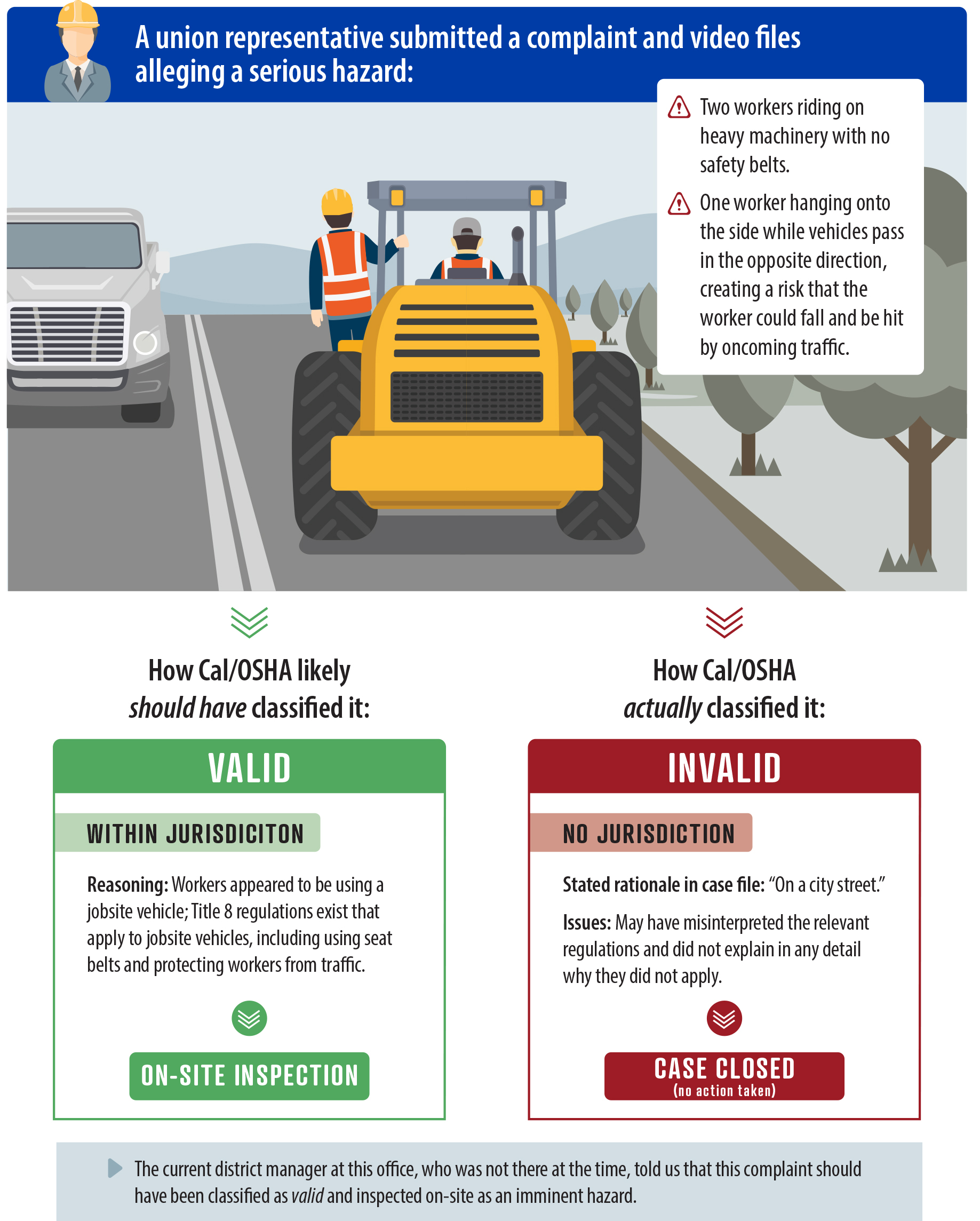

In one case that we depict in Figure 5, a worker was hanging onto the side of a moving construction vehicle in a manner that risked the worker falling off and potentially being hit by oncoming traffic. Cal/OSHA considered the complaint to be outside of its jurisdiction and therefore invalid, so Cal/OSHA closed the case without investigating. However, the case file included only minimal explanation of Cal/OSHA’s reasoning, and our assessment of the complaint led us to conclude that it was likely within Cal/OSHA’s jurisdiction. The case file also did not include evidence that the district office had consulted with the legal unit to confirm that Cal/OSHA did not have jurisdiction in this case, even though Cal/OSHA’s policy states that district offices should do so if they have questions about jurisdiction at a particular worksite. As a result of its determination that the complaint was invalid, Cal/OSHA did not follow up with the employer at all and hazards may have conceivably continued to pose risks to workers at that worksite.

Figure 5

Cal/OSHA Classified a Complaint as Invalid and Took No Further Action, but the Complaint Was Likely Valid and Within Its Jurisdiction

Source: Case file, regulations, Cal/OSHA policies and procedures, and interviews with the current district manager.

A union representative submitted a complaint and video files alleging a serious hazard:

• Two workers riding on heavy machinery with no safety belts.

• One worker hanging onto the side while vehicles pass in the opposite direction, creating a risk that the worker could fall and be hit by oncoming traffic.

How Cal/OSHA likely should have classified the complaint: <h1>

Valid-Within Jurisdiction <h2>

Our reasoning is that the workers appeared to be using a jobsite vehicle; and Title 8 regulations exist that apply to jobsite vehicles, including using seat belts and protecting workers from traffic. The case likely should have resulted in an on-site inspection.

How Cal/OSHA actually classified the complaint: <h1>

Invalid: No jurisdiction <h2>

The stated rationale in the case file was, “On a city street.” The issues included that Cal/OSHA may have misinterpreted the relevant regulations and did not explain in any detail why they did not apply. Cal/OSHA closed the case without taking any further action.

The current district manager at this office, who was not there at the time, told us that this complaint should have been classified as valid and inspected on-site as an imminent hazard.

Similarly, as we show in Figure 6, Cal/OSHA investigated a heat‑related complaint by sending a letter to the employer when policy required it to have inspected on‑site. According to the current regional manager, the rationale documented in the case file for not inspecting—manager discretion—had no basis in Cal/OSHA policy and would not have been an option based on the specifics of the complaint. Moreover, the regional manager stated that because the complainant referenced a heat illness, the district office should have completed an accident report and followed the inspection procedures under Cal/OSHA’s heat illness prevention special emphasis program. Because it did not conduct an on‑site inspection, Cal/OSHA may have missed opportunities to issue citations, assess fines, and ensure that the employer corrected the hazard—a hazard that had already generated two complaints and resulted in a worker receiving emergency medical treatment.

Figure 6

Cal/OSHA Investigated a Complaint by Letter When Its Policies Required an On‑Site Inspection

Source: Complaint case files and related records and Cal/OSHA policies and procedures.

A worker made a complaint to Cal/OSHA alleging that the employer had failed to fix the air conditioning system, meaning that the temperature of the kitchen in which the employee worked exceeded 90 degrees at times. The complaint also alleged that ventilation in the kitchen was poor, putting employees at risk of breathing smoke. The worker may have suffered heat illness and was taken to the ER by ambulance.

Two different Cal/OSHA policies required an on-site inspection:

Policy #1 <h1>

Cal/OSHA should always inspect on-site when the complainant is a current employee who provides their name and address and the hazard is serious. The complainant in this case appeared to be a current employee who provided a name and address. Cal/OSHA categorized the alleged hazards as serious.

Policy #2 <h1>

Cal/OSHA should inspect on-site all indoor heat-related complaints when the complainant is a current employee who provides their name and address. The complaint referenced heat-related concerns in an indoor environment.

Other context <h1>

In addition, Cal/OSHA received a similar complaint about the same employer’s air conditioning system a few months earlier. Cal/OSHA sent a letter to the employer instead of inspecting on-site. According to case records, the employer had yet to respond to that letter to explain how they had addressed the hazard.

Despite these factors, Cal/OSHA sent the employer another letter rather than inspecting on-site.

• Rationale stated in case file: “[Manager] discretion”

• The employer did not provide evidence, such as repair invoices, to show that they corrected the hazards when it responded to Cal/OSHA’s second letter investigation.

Managers explained that understaffing sometimes contributed to their decisions to investigate with a letter rather than inspect on‑site. For example, in one case that Cal/OSHA categorized as a serious hazard—in which a complainant alleged that the employer was operating a machine without proper guards—the district manager told us that if the district office had been fully staffed, he would have assigned the complaint for inspection. In the two‑month span of time during which the district office received the complaint, the office fielded 470 total complaints, accidents, and referrals and likely had vacancies in about half of its 15 total staff positions. Nevertheless, none of the case files we reviewed documented understaffing as a factor in the district office’s decision not to inspect a complaint, and the absence of that rationale contributes to a lack of transparency in Cal/OSHA’s decision‑making practices.

Another possible cause for Cal/OSHA’s decisions not clearly aligning with its own policy requirements is that in certain of the nine cases, these decisions may have potentially complied with policy, but district offices did not document evidence to demonstrate their compliance. In our follow‑up discussions with regional and district managers about the case files, some of the managers agreed that Cal/OSHA should have inspected certain complaints we reviewed. However, other managers indicated that their offices’ decisions had complied with policy. For instance, one manager told us that a complainant must have agreed to Cal/OSHA conducting a letter investigation instead of an on‑site inspection, which would have made Cal/OSHA’s decision not to inspect that case compliant with policy. Nevertheless, the case file did not contain any evidence of the complainant’s agreement. In another case we reviewed, the district manager told us that the complainant had not been an official union representative of employees at the worksite, which meant that Cal/OSHA policy did not require an inspection. However, the district office did not document or explain these details about the complainant in the case file, raising questions about their validity. Currently, Cal/OSHA’s policies do not require district offices to explain their reasoning in detail—such as how their decisions align with each relevant component of policy—when they decide not to inspect. Cal/OSHA leadership told us that the division is in the process of rewriting its policies to ensure that enforcement personnel explain in detail their reasons for not conducting on‑site inspections of complaints.

In at Least Five Cases, Cal/OSHA Followed Its Policies in Deciding to Investigate by Letter, but Those Policies Are Flawed

In at least five of the 24 letter investigation cases we reviewed, Cal/OSHA followed its policies in deciding not to inspect on‑site, but there were factors indicating that inspections may have benefited workers more than the letter investigations did. For example, these factors included complaints that alleged a worker injury, complaints with observable hazards that could have posed harm to workers, and a complaint in which the employer had a history of a previous complaint.

The text box describes one of these complaints. Cal/OSHA’s decision not to inspect aligned with policy because the complainant submitted the complaint anonymously. However, whether a complaint is anonymous should not be a critical determining factor in whether to conduct an on‑site inspection because complainants may have legitimate reasons for not wanting to identify themselves, such as a fear of employer retaliation.

Example of a Complaint for Which an On‑Site Inspection May Have Been Beneficial

An employee submitted a complaint to Cal/OSHA about an employer that operated a warehouse.

- Main hazards alleged: Employees use machinery unsafely, such as by standing on the tops of forklifts to access inventory. Employees are not required to wear steel‑toed boots or safety vests.

- Additional context: The complaint mentioned an employee who broke a leg while moving boxes. Cal/OSHA had also received a previous complaint related to the employer’s forklift safety and had not inspected it on‑site.

- Cal/OSHA’s documented reasons for not inspecting: The complainant was anonymous, making the complaint non‑formal, and thus not requiring inspection.

- Outcome: Cal/OSHA sent a letter to the employer. The employer responded that the hazards were not present, but it did not provide supporting documentation for that claim, such as photographs or safety policies.

Source: Complaint case file.

For deciding whether to investigate complaints by letter or to inspect on‑site, Cal/OSHA’s policies generally place more emphasis on the source of the complaint than they do on other factors, such as the alleged hazards, the employer’s history, and the potential benefits of an on‑site inspection relative to the specific circumstances of the complaint. Cal/OSHA’s data also indicate as much: from fiscal years 2019–20 through 2023–24, it conducted inspections of nearly two‑thirds of the valid complaints that it classified as formal—for example, if the complainant was a current employee who provided Cal/OSHA with their name and address. By contrast, it conducted inspections of only about one‑third of the valid complaints that it classified as alleging an imminent or serious hazard. In other words, the source of the complaint has a larger impact on Cal/OSHA’s decision about whether to inspect on‑site than does the severity of the allegations. In three of the cases we reviewed, Cal/OSHA did not inspect the complaint primarily because the complainant was anonymous, and the case file did not demonstrate whether other circumstances of the complaint made it suitable for a letter investigation. In two other cases, the complainant apparently agreed to a letter investigation, in which case Cal/OSHA’s policy allows district offices to classify the complaints as non‑formal even if the alleged hazards may otherwise have warranted an inspection. Changing its policies to require staff to more explicitly weigh factors in addition to the source of the complaint would help Cal/OSHA better justify its choice to investigate with a letter and might also lead to Cal/OSHA inspecting more employers on‑site when doing so could benefit workplace safety.

Cal/OSHA leadership agreed that factors like the severity of a complainant’s allegations are important for enforcement personnel to assess and stated that personnel already consider severity when evaluating complaints. They told us that Cal/OSHA is in the process of rewriting its policies and procedures for clarity and to ensure that enforcement personnel work toward the goal of conducting on‑site inspections of complaints that allege serious hazards, regardless of whether the complaint is formal or non‑formal.

For Complaints Investigated by Letter, Cal/OSHA Often Did Not Require Evidence That Employers Had Addressed All Alleged Hazards

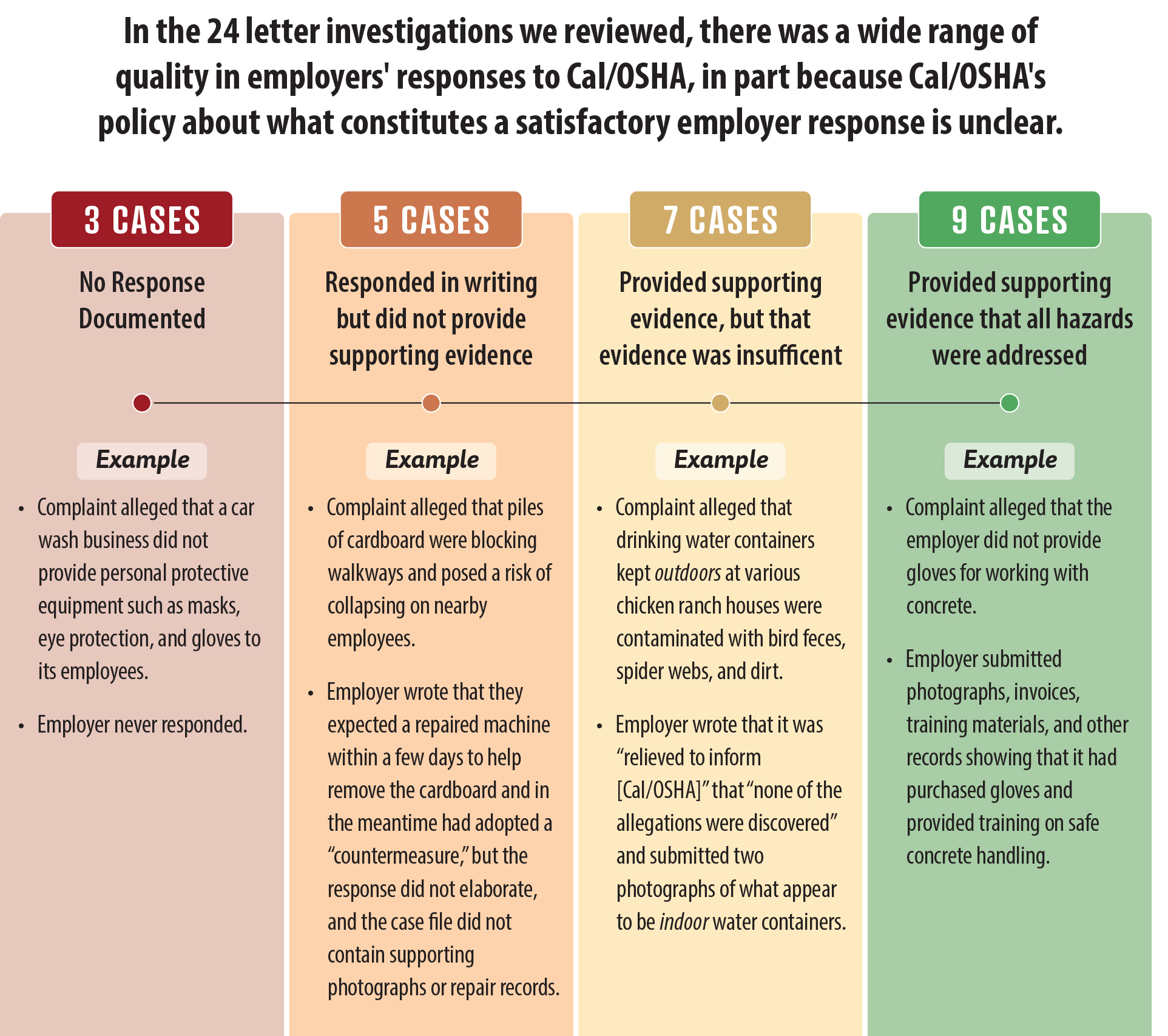

When Cal/OSHA conducts a letter investigation, the district office must request a written response from the employer within a specified time frame and document that this response is satisfactory. Cal/OSHA’s policy states that if the response is not satisfactory, the office should inspect the employer on‑site. However, as Figure 7 shows, employers’ responses to the letter investigations we reviewed varied significantly in quality, yet Cal/OSHA closed all these cases without inspecting on‑site. For instance, Cal/OSHA closed three of the 24 cases even though the case files did not include a response from the employer addressing the concerns raised. Overall, in 15 of 24 letter investigations, Cal/OSHA closed complaint cases without clear supporting evidence that the employer addressed all the alleged hazards.

Figure 7

Cal/OSHA Closed Some Letter Investigations Without Sufficient Evidence That the Employers Had Addressed All Alleged Hazards

Source: Case files, Cal/OSHA policies and procedures, and interviews with Cal/OSHA officials.

In the 24 letter investigations we reviewed, there was a wide range of quality in employers’ responses to Cal/OSHA, in part because Cal/OSHA’s policy about what constitutes a satisfactory employer response is unclear.

No response documented: 3 cases <h1>

Example: <h2>

• Complaint alleged that a car wash business did not provide personal protective equipment such as masks, eye protection, and gloves to its employees.

• Employer never responded.

Responded in writing but did not provide supporting evidence: 5 cases <h1>

Example: <h2>

• Complaint alleged that piles of cardboard were blocking walkways and posed a risk of collapsing on nearby employees.

• Employer wrote that they expected a repaired machine within a few days to help remove the cardboard and in the meantime had adopted a “countermeasure,” but the response did not elaborate, and the case file did not contain supporting photographs or repair records.

Provided supporting evidence, but that evidence was insufficient: 7 cases <h1>

Example: <h2>

• Complaint alleged that drinking water containers kept outdoors at various chicken ranch houses were contaminated with bird feces, spider webs, and dirt.

• Employer wrote that it was “relieved to inform [Cal/OSHA]” that “none of the allegations were discovered” and submitted two photographs of what appear to be indoor water containers.

Provided supporting evidence that all hazards were addressed: 9 cases

Example: <h2>

• Complaint alleged that the employer did not provide gloves for working with concrete.

• Employer submitted photographs, invoices, training materials, and other records showing that it had purchased gloves and provided training on safe concrete handling.

Cal/OSHA’s policy for handling letter investigations is unclear about what constitutes a satisfactory employer response. For example, one section of the policy requires that Cal/OSHA’s letter inform the employer that the employer’s response must describe the results of its investigation, explain corrective actions taken, and include evidence that documents hazard correction, such as photographs, video, or invoices. However, the section of the policy that relates to Cal/OSHA evaluating the employer’s response does not specify that the employer must submit evidence, and it instead defines a satisfactory response as “one which indicates that the employer performed an investigation of the complaint items and either determined that a hazard was present and undertook appropriate corrective actions, or determined that no hazard was present.” As a result of this vagueness in policy, the district and regional managers we spoke with shared different opinions about what the policy required. For instance, one regional manager told us that Cal/OSHA’s letter to the employer always requests that the employer include in its response documentation to support its corrective measures but that this documentation is preferred rather than absolutely required. Another district manager stated that for one case we reviewed—one for which the employer’s response did not contain any supporting documents—he considered the response satisfactory based on his understanding of the alleged hazards and the type of worksite in which they occurred.

Although some of the complaints that we summarize in Figure 7 alleged hazards that did not appear to be dangerous—for example, pest control issues or unreliable running water for hand‑washing—others described situations with substantial risks for injury or illness. In one case, a complainant alleged that a beverage manufacturer was operating a machine with the guard doors open, which the Cal/OSHA district office determined was a serious hazard. An inspector at the district office requested from the employer and included in the case file several photographs of the machine. However, the photographs were unclear—for example, some were not close enough to the machine to see it in detail—and the case file did not include a note from the employer or inspector explaining the photographs. The district manager told us that the inspector who evaluated the employer’s response was newly hired and that if the district office had more staff, it could have better trained the inspector to request clearer photographs. When Cal/OSHA does not ensure that employers’ responses are complete and supported with evidence that the employers’ assertions are true regarding the alleged hazards and their correction, it reduces assurances that letter investigations fully mitigated the potential harms to workers. Even for complaints that allege less serious hazards, ensuring that employers appropriately responded to these hazards would help Cal/OSHA hold employers accountable for workplace safety and demonstrate that it is responsive to workers’ concerns.

Cal/OSHA policy includes two additional mechanisms that are intended to help district offices minimize the risk that employers do not correct hazards, but these mechanisms have flaws. First, district offices are supposed to send a letter to the complainant about the employer’s response to the letter investigation. The template for this letter invites complainants to contact Cal/OSHA if they do not agree with the findings and states that if Cal/OSHA does not hear from the complainant, it will assume that the employer adequately corrected the hazards. However, relying on further response from the complainant to identify ongoing hazards places significant burden on the complainant and does not work for cases with anonymous complainants. Second, Cal/OSHA policy allows, but does not require, the district manager to select a specified percentage of satisfactory employer responses to inspect on‑site to verify that the employer corrected the hazards. A 2024 workload study of Cal/OSHA’s inspector positions pointed out that these types of inspections are important because the chance of them occurring encourages compliance from employers, and the study found that Cal/OSHA had an unmet need for hundreds more of these inspections annually. Several district managers indicated that they lacked the staff necessary to conduct these follow‑up inspections given the higher‑priority inspections they had to handle. We discuss understaffing more fully later in this report.

In addition to requiring written responses from employers who receive letter investigations, Cal/OSHA requires that employers respond in a timely manner—within five working days of receiving a letter for complaints alleging serious hazards and within 14 calendar days for non‑serious complaints.2 Employers did not submit timely responses in 11 of the 24 letter investigations we reviewed, reducing assurances that they had taken prompt action to protect their workers. Three employers among those 11 cases did not respond at all, and two others took more than 50 days to respond. Managers shared that the primarily paper‑based case management system, coupled with too few office technicians, made it difficult to track letter investigation deadlines or to know for certain the date that the employer received Cal/OSHA’s letter in the mail—or if they received it at all. However, one district manager told us that the office sends letters via email to have a record of the date that the employer received the letter. Calling employers before sending letters may also help: Of the five letter investigations we reviewed involving serious hazards—those for which policy requires phone contact with the employer—each employer responded within the deadlines.

Cal/OSHA Did Not Sufficiently Document Its Decisions Not to Inspect Some Accidents We Reviewed

Cal/OSHA’s process for determining whether to conduct an on‑site inspection of reported workplace accidents differs from its process for complaints. As the text box describes, state law requires that Cal/OSHA investigate certain accidents—unless it determines that an investigation is unnecessary and explains its reasoning—and gives it broad authority to investigate others. Whereas Cal/OSHA conducts investigations by letter for some complaints, Cal/OSHA does not do so for accidents, which means that it either conducts an on‑site inspection of accidents or it takes no further action.

State Law Gives Cal/OSHA Broad Authority for Conducting Accident Investigations

1. Cal/OSHA shall investigate the causes of any employment accident that is fatal to one or more employees or that results in a serious injury or illness, or a serious exposure, unless it determines that an investigation is unnecessary. If the division determines that an investigation is unnecessary, it shall summarize the facts indicating so and the means by which the facts were determined.

a. State law defines “serious injury or illness” to include injuries that require inpatient hospitalization, for other than medical observation or diagnostic testing, or in which an employee suffers … serious permanent disfigurement.

2. Cal/OSHA may investigate the causes of any other industrial accident or occupational illness which occurs within the state …

[Emphasis added]

Source: Labor Code sections 6302 and 6313.

To determine whether Cal/OSHA documented logical reasons for not conducting on‑site inspections of reported accidents, we selected for review seven uninspected accidents with injury descriptions that concerned us. In six of the seven cases we reviewed, the case files lacked documentation to support Cal/OSHA’s decision not to inspect. These six cases included injuries and illnesses that ranged from apparent heat illnesses requiring emergency medical treatment to lacerations that required hospital care or even surgery. The text box describes two of these cases. When we spoke with district managers about these cases, they provided additional context—context that was not documented in the case files—for why the cases may not have warranted an inspection. For example, the district manager for the office that handled Case Example 1 told us that the worker appeared to have been wearing personal protective equipment, creating less reason to suspect that the employer violated safety regulations. However, the case file did not document this reasoning, which enforcement personnel could have done by, for example, explaining which safety regulations would have applied or by explaining how surgery and an overnight hospital stay did not constitute a serious injury. In Case Example 2, the district manager indicated that the worker had likely not been formally admitted for inpatient hospital care, meaning that state law did not consider the injury to be serious. Even so, the one‑page case file referenced an outdated statutory requirement about the number of hours of hospital care and did not include any medical records as supporting evidence. By not inspecting cases such as these, Cal/OSHA may be missing opportunities to hold employers accountable for harm that their workers experience.

Cal/OSHA Did Not Inspect Some Accidents, Even Though an Inspection May Have Helped Protect Workers

Examples of accidents reported to Cal/OSHA that it decided not to inspect:

Case Example 1: An employee suffered a laceration on his shin from a chainsaw, resulting in surgery, an overnight hospital stay, and six weeks of recovery.

- The case file merely cited Labor Code section 6313, which we show in the previous text box, as reason not to conduct an on‑site inspection. However, the injury appeared to meet the definition of serious in state law, and the file did not include an explanation of why the injury was not considered serious or, if it was, why an inspection was unnecessary.

Case Example 2: An accident report stated than an employee was struck in the head by an object, resulting in a skull fracture that rendered the employee unconscious for five to ten minutes.

- The report referred to the injury as serious but stated that the employee was in the hospital for only nine hours, so there was no inspection. The case file referenced an outdated requirement and did not include medical records or other evidence to support that the injury did not meet the definition of serious in state law.

Source: Accident case files.

In two other cases, Cal/OSHA’s policy for handling heat‑related accidents appeared to require an on‑site inspection, but Cal/OSHA did not conduct one. Cal/OSHA has a heat illness prevention special emphasis program (heat policy) that was active at the time of both accidents and generally requires on‑site inspections of accidents that are related to heat illness. In one case we reviewed, the accident report listed the incident as “heat illness” and stated that the employee “became disoriented and vomited,” “was reportedly ‘in and out of consciousness,’” and had not had any water to drink that day—all of which align closely with indicators in the heat policy that would require an inspection. However, the case file did not document any consideration of the heat policy to support Cal/OSHA’s decision not to inspect. Instead, the file noted that Cal/OSHA’s reason for not inspecting was that the injury was not considered serious, because the worker was taken to the emergency room for observation only and was not formally admitted for inpatient hospital care. A senior safety engineer from the district office that handled the case also told us that the office had visited the worksite many times and knew from experience that the employer provides water for its workers. However, the senior safety engineer agreed that the heat policy requires on‑site inspections of any suspected heat illnesses. Further, about four months after the accident occurred, a worker at the same worksite “collapsed from apparent heat exhaustion” and was taken by ambulance to a hospital.

Understaffing was one of the causes that contributed to the issues we identified. Every district manager we contacted regarding uninspected accidents stated that they were short‑staffed and that this affected their ability to do their work. For instance, in Case Example 1 in the previous text box, even though the district manager provided context for why an inspection may not have been warranted, the district manager told us that limited staffing was also one reason the district office did not conduct an inspection. The district manager indicated that the office would like to inspect more cases but lacks the staff to do so and must focus on the cases that have the highest impact on employee health and safety. We discuss Cal/OSHA’s understaffing in more detail later in this report.

Nevertheless, Cal/OSHA should also make changes to its policies and processes to ensure that it conducts inspections of accidents whenever appropriate. Given Cal/OSHA’s broad authority for inspecting accidents, we would have expected it to have guidelines for how to determine whether an on‑site inspection of an accident is warranted and how to document the specific reasons for that determination. However, Cal/OSHA’s policies do not specify any process for inspecting accidents that are not considered serious under state law. For example, one of its policies lists priorities for each type of inspection that Cal/OSHA may conduct, such as prioritizing inspections of imminent hazard complaints and fatal accidents above inspections of other types of complaints and accidents. However, this priority list does not mention inspecting accidents with non‑serious injuries, even though these types of accidents may still reflect dangerous hazards that pose risks to workers. In one case file we reviewed, a fire captain reported to Cal/OSHA an accident involving an electric shock, but the district office processed the case as a complaint instead of an accident and conducted a letter investigation. According to the district manager, the district office processed the case as a complaint because the accident was non‑serious—meaning that Cal/OSHA was not required to investigate it—but the office wanted to investigate anyway to ensure that the employer addressed the hazard. One reason that enforcement personnel may classify accidents as complaints just to investigate them further is because Cal/OSHA’s complaint policies have more options and guidelines for investigating less serious hazards. For instance, Cal/OSHA’s accident policies do not include guidelines for considering factors beyond the severity of the worker’s injury when determining whether an inspection would be beneficial for workplace safety. In particular, the policies do not require personnel to consider the likelihood that an inspection could identify a workplace violation that poses risks to workers. Such guidelines would help Cal/OSHA inspect more accidents that fall below the high threshold in state law for mandatory investigations yet still represent a potential risk for workers.

Even for the process of simply determining whether state law requires accident investigations, Cal/OSHA policies contain little guidance about how district offices should document their reasons for not inspecting, such as whether district offices should include medical records as support, a practice that we found varied by case file. For example, in at least three cases we reviewed—such as the reported skull fracture that we describe as Case Example 2 in the text box earlier—workers had apparently received care at a hospital, but that care may not have been classified as inpatient care, raising questions about whether the injuries met the definition of serious in state law. One senior safety engineer told us that the district office relies on the hospital’s determination about whether to admit a patient for inpatient treatment. Even so, none of those three case files included medical records or other supporting evidence that indicated whether the care provided was inpatient care, likely because Cal/OSHA policy does not require this type of documentation. In addition, the accident report forms in case files we reviewed often left room for only short phrases such as “[Labor Code section] 6313” or “no serious injury,” rather than more detailed and helpful reasoning.

When It Does Perform Inspections, Cal/OSHA’s Process Has Critical Weaknesses

Key Points

- When Cal/OSHA did conduct on‑site inspections, those inspections were not always thorough and effective. For example, Cal/OSHA enforcement personnel did not consistently document effective reviews of employers’ injury and illness prevention programs (IIPP)—which provide key safeguards against dangerous hazards—nor did they always include detailed and legible notes from interviews they conducted with workers. In one fatal accident we reviewed, the case file included the employer’s IIPP but did not contain any documentation that the inspector had evaluated it or its implementation, even though there were indications that an IIPP violation may have occurred.

- Cal/OSHA took weeks or even months to initiate some complaint and accident inspections, which can hinder its ability to gather relevant evidence and identify violations that have put workers at risk. In four of our 15 selected complaints, Cal/OSHA began the inspections after the deadlines in state law, ranging from about one week late to about two months late. In addition, Cal/OSHA initiated three non‑fatal accident inspections we reviewed one month or more after the accidents had occurred.

Cal/OSHA’s Inspections Varied in Their Thoroughness and Effectiveness

We reviewed 15 complaints that received an on‑site inspection and found that the inspections did not always adhere to Cal/OSHA’s policies for gathering, documenting, and organizing evidence. We also reviewed eight reports of accidents that Cal/OSHA inspected and found some of the same shortcomings. Figure 8 highlights our concerns.

Figure 8

Case Files Did Not Always Document That Cal/OSHA Had Followed Important Aspects of Its Inspection Process

Source: State law, Cal/OSHA policies and procedures, and case files.

We provide three examples of inspection steps in Cal/OSHA’s policies for which we identified deficiencies. Case files we reviewed involving accident inspections contained similar deficiencies.

1. Evaluate the employer’s IIPP and how well the employer is implementing that program, which ensures that employers maintain effective safety programs that protect their workers.

• Seven of the 15 complaint inspections we reviewed did not include any IIPP-related violations and lacked a complete IIPP evaluation in the case file, causing us to question whether the inspection may have overlooked potential violations.

2. Record audio of interviews or obtain signed statements when possible; otherwise, document legible interview notes. These steps help ensure that Cal/OSHA develops strong evidence to support the violations it identifies.

• Only one of the 15 complaint case files included audio recordings or a signed statement from an interviewee.

• Five of the 15 case files contained interview notes that were difficult to read, overly brief, undated, or unclear as to which individual made each statement.

3. Organize evidence and explain each element of a violation, which ensures that the violation is founded and is likely to withstand an appeal by the employer.

• In five of our 11 selected complaints that included citations, the relevant worksheets were incomplete, raising questions about whether Cal/OSHA had obtained sufficient evidence to support the violations.

For instance, Cal/OSHA’s inspections did not consistently document thorough reviews of employers’ safety programs as both law and policy mandate. State law requires every employer to establish, implement, and maintain an effective IIPP. The IIPP is a written plan intended to prevent injuries and illnesses by establishing methods to identify and correct hazards and by ensuring that employees comply with safe workplace practices. Every Cal/OSHA inspection is supposed to include an evaluation of the employer’s IIPP, and 34 percent of on‑site inspections that occurred during our audit period and resulted in a citation identified at least one IIPP‑related violation. Evaluating an employer’s IIPP and identifying related violations can be an important way to ensure that the employer’s underlying safety culture and practices are effective at protecting workers and preventing injuries and illnesses. Figure 9 shows that despite the importance of thoroughly evaluating the IIPP, the case files we reviewed did not demonstrate that Cal/OSHA always did so.

Figure 9

Cal/OSHA Did Not Always Document Thorough Evaluations of Employers’ Safety Programs, Missing Opportunities to Better Protect Workers

Source: State law, Cal/OSHA policies and procedures, and complaint and accident case files.

Every employer must implement an effective injury and illness prevention program (IIPP) that includes several key elements, such as:

• A compliance system (discipline, re-training, etc.).

• A communication system (to and from employees).

• Procedures for conducting periodic safety inspections.

• Procedures for investigating injuries or illnesses.

• Procedures for correcting unsafe conditions.

• Provisions of training and instruction.

Every on-site inspection that Cal/OSHA conducts must include an evaluation of the employer’s IIPP. For example, does implementation of the employer’s safety inspection procedures result in a comprehensive evaluation of the hazards present at the workplace? The IIPP evaluation entails:

• Ensuring that the employer’s IIPP contains required elements.

• Interviewing a sample of employees.

• Considering the effectiveness of the IIPP’s implementation in practice.

We provide case examples that range from sufficient IIPP analyses to insufficient IIPP analyses:

Case Example #1 – Accident (fatality) <h1>

• Documented and evaluated the employer’s written IIPP using a basic checklist.

• Interviewed workers and management about the IIPP’s effectiveness.

• Explained in the case file how the IIPP had been ineffective in practice.

• Result: Cited the employer for an IIPP-related violation and documented changes the employer made to improve its safety program.

Case Example #2 – Complaint <h1>

• Documented and evaluated the employer’s written IIPP using a basic checklist.

• Did not document any interviews about the IIPP’s effectiveness.

• Did not evaluate in the case file the IIPP’s implementation in practice.

• Result: Did not cite the employer for any IIPP-related violations, and it was unclear whether any were warranted.

Case Example #3 – Accident (fatality) <h1>

• Documented the employer’s written IIPP but did not evaluate it using a basic checklist.

• Documented brief notes from only two interviews, and the notes contained information that was only indirectly related to the IIPP’s effectiveness.

• Did not evaluate in the case file the IIPP’s implementation in practice.

• Result: Did not cite the employer for any IIPP-related violations, even though there were indications that violations may have existed.

We found similar issues in multiple accident inspections we reviewed, which was particularly concerning because it was unclear whether deficient employer safety programs may have contributed to workers’ deaths and injuries. For example, in one fatal accident we describe in Figure 9, the case file included the employer’s written IIPP but did not contain any documentation that the inspector had evaluated it or its implementation, and Cal/OSHA did not issue any citations related to the IIPP. However, there were indications in the case file that an IIPP violation may have occurred. For instance, the inspector’s interview notes mentioned that it was “common practice” for employees to operate equipment in an unsafe manner. Further, Cal/OSHA cited the same employer for an IIPP‑related violation after inspecting another fatal accident at a different worksite just a few months later.

Some district managers told us that inspectors are familiar with IIPP requirements and analyze the effectiveness of the IIPP even if they may not document this analysis in the case file. One manager indicated that checklists or similar forms do not capture the complexity of an effective IIPP analysis and can be a paperwork burden for inspectors. Cal/OSHA policy contains detailed guidelines for these IIPP analyses but does not specify how to document them. Without some level of documentation, Cal/OSHA cannot demonstrate that inspectors are conducting reviews of the IIPP as required, which increases the risk that they may overlook IIPP violations that put workers in harm’s way.

Similarly, Cal/OSHA may not have interviewed enough workers in about half our selected complaint inspections and did not always interview witnesses or workers most familiar with the alleged violations. Cal/OSHA inspectors use witness statements as evidence to document the existence of a violation. State law and Cal/OSHA’s procedures require inspectors to interview a “sample” of employees—which Cal/OSHA policy further specifies must include supervisors—as part of any evaluation of an employer’s IIPP. However, neither state law nor Cal/OSHA policy provides a number or percentage of employees that would constitute a representative sample. In three of our 15 selected complaint inspections, inspectors conducted only a single interview; in two of these cases, the sole interviewee was a manager. Without interviews from a variety of sources, Cal/OSHA may miss crucial perspectives and sources of evidence.

Further, when Cal/OSHA did conduct interviews, it did not always correctly document them, weakening the interviews’ reliability as evidence. Cal/OSHA’s inspection policies direct inspectors to try to record audio of all interviews or to obtain signed, written statements from interviewees whenever possible. If interviewees refuse to allow audio recording or to provide a written statement, inspectors must thoroughly and legibly document all statements on a note‑taking sheet. In addition, when interviewing non‑English‑speaking workers, inspectors must use appropriate language translators—either DIR‑certified bilingual employees or individuals available through a contracted language translation vendor. However, Cal/OSHA did not ensure that inspectors followed all these policies when conducting and documenting interviews. For example, five complaint inspection case files contained interview notes that were difficult to read, overly brief, undated, or unclear as to which individual made each statement. Five of the complaint inspections also likely included interviews conducted in a language other than English, but none of these five case files included clear documentation that the interviews involved an appropriate translator. When we spoke with Cal/OSHA’s chief and deputy chief about these issues, they told us that many workers are not comfortable being recorded but acknowledged that Cal/OSHA could change its interview training and guidance to emphasize the importance of recording interviews when possible. The chief and deputy chief added that when Cal/OSHA transitions to using an electronic case management system, that system will help ensure that interview notes are legible and easily accessible.

Issues with Cal/OSHA’s documentation of interviews and other evidence were sometimes made worse because inspectors did not clearly explain how the evidence they had collected supported a violation. Cal/OSHA policy requires inspectors to determine during an on‑site inspection whether the employer violated each required element of a regulation and to complete violation worksheets that help identify and organize the evidence proving the violation. Doing so can help ensure that Cal/OSHA issues citations that are fair and will withstand an employer’s appeal. However, these worksheets were not always complete, reducing assurances that Cal/OSHA could support the violations with appropriate evidence. In three complaint cases we reviewed, inspectors used different versions of the worksheet that required fewer details and did not include fields to explain the supporting evidence. One case file was missing three of the worksheet’s five pages, omitting most elements of the violated regulation and the description of the supporting evidence. In one of the fatal accidents we reviewed, the case file did not contain any violation worksheets at all. After the employer appealed, Cal/OSHA reduced the only violation it had found from a serious accident‑related violation to a general violation with a $600 fine.

Broader underlying problems with Cal/OSHA’s processes and staffing levels, which we discuss in more detail later in the report, likely contributed to the inspection deficiencies we identified. For example, some district managers told us that understaffing contributed to incomplete case files and that they had limited time to review inspectors’ work because of high caseloads. A 2023 internal audit found that Cal/OSHA’s inspection case files were not always complete. This finding cited some files that were missing documentation related to interview notes and violation worksheets, and it indicated that outdated policies and multiple versions of some forms were part of the problem. The internal audit also noted that only nine of 17 district managers had taken formal training on case management and review.

Cal/OSHA Did Not Initiate Some Inspections in a Timely Manner, and the Appeal Process Often Significantly Delayed Case Closures

Cal/OSHA did not start all its complaint inspections in a timely manner, which can subject workers to ongoing risks and make it more difficult for Cal/OSHA to identify workplace violations and collect evidence. When Cal/OSHA receives a complaint of an unsafe workplace from an employee or an employee’s representative, state law requires the division to investigate within three working days for complaints alleging serious violations and within 14 calendar days for those alleging non‑serious violations. Cal/OSHA policy further requires investigation of imminent hazard complaints within 24 hours.3 As the text box shows, Cal/OSHA initiated four of our 15 selected complaint inspections after the deadlines in state law. More broadly, the rate at which Cal/OSHA started inspections after these deadlines varied by the severity of the complaint. As we show in Appendix A, Table A.9, for valid complaints it inspected in fiscal year 2023–24, Cal/OSHA initiated inspections of 9 percent of imminent hazard complaints after two days, 25 percent of serious complaints after six days, and 41 percent of other complaints after 15 days.

Cal/OSHA Missed Deadlines to Inspect Four of Our 15 Selected Complaints

Case #1: Failure to Report Amputated Finger

Complaint Received: 7/19/22*

Inspection Due: 8/2/22

Site Inspected: 8/24/22 (~3 weeks late)

Case #2: Lack of Fall Protection (& Others)

Complaint Received: 2/5/24†

Inspection Due: 2/19/24

Site Inspected: 2/23/24 (~1 week late)

Case #3: Failure to Report Injury From Fall

Complaint Received: 12/5/22

Inspection Due: 12/8/22